The Female Factor

THE FEMALE FACTOR: LESSONS WE CAN LEARN FROM COUNTRIES WITH HIGH PERCENTAGES OF WOMEN GOLFERS

BY STINA STERNBERG, GOLF DIGEST GLOBAL GOLF DIRECTOR

Over the last 20 years, the American golf industry has spent an impressive amount of time and resources on initiatives designed to bring more women to the game. Unfortunately, those efforts have yielded little; the number of women who play golf in this country is the same today as it was in 1991—roughly 5 million, or 20 percent of all participants.Five million may sound like an imposing number, but when you compare our 20-percent female proportion to other sports, it becomes clear just how gender-imbalanced golf is in America. Both bowling and tennis draw 48 percent female participants in this country. Skiing has 49 percent women, billiards 40 percent, fishing 31 percent and handgun shooting 29 percent. In fact, golf’s numbers are on par with ice hockey, paintball and mixed martial arts.Up to 40 percent of new golfers are women, and have been for a long time. Clearly, the interest is there—American women want to pick up the game, and many do—but once they experience it, too many leave. Countless studies have been done to determine what drives women away from our sport, and the answers typically range from time and expense to the game’s difficulty and its inherently intimidating atmosphere. National, regional and local programs from every organization in golf have attempted to alleviate some of these issues, to little or no avail. Maybe golf just isn’t a sport for women?

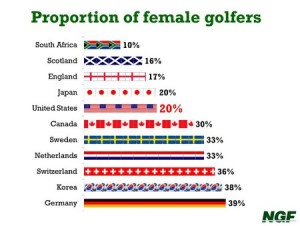

Not so fast. A quick look around the world will tell you that in many other golf nations, women’s participation is as high as 40 percent of all golfers. What do these countries do differently than America? How are they so successful at keeping women in the game? The information gathered for this article was obtained through conversations with representatives from golf organizations and golf media in over 20 countries, and is focused especially on five nations that do very well with women: Sweden (which has 33 percent female participants), Germany (39 percent), the Netherlands (35 percent), Canada (30 percent) and South Korea (38 percent).

Click here to enlarge the image.

1. The buck stops here

The majority of countries that do well with women golfers have an overriding agency or federation that’s responsible for the sport and its national growth. In some cases it’s a government recognized entity with funding from the nation’s Olympic Committee, but not always. What these agencies or national federations have in common is that golfers contribute to them financially when they register to play golf or become members of a golf club. In many of these countries, even public golfers are required to register with the federation through the club or course at which they play.

The registration fees are small—in Holland it’s the equivalent of about $20 per adult golfer per year, in Sweden it’s around $25 — but the money adds up for the federations. In return, the agency or federation promotes golf and establishes programs for emerging golfers of all ages and genders, but especially juniors and women. In Canada, golf is governed by Golf Canada, which reports to a federal agency called Sport Canada, and they have to fulfill certain mandates to remain part of that family and retain funding.

Sport Canada considers women an underserved part of the golf population—even at 30 percent—so Golf Canada goes after women in a big way. Golf Canada has data that shows if girls aren’t exposed to a sport like golf between the ages of 6 and 12, the chances of their picking up that sport later drop significantly. Hence, a prime focus for Golf Canada is to reach young girls early, which they do through the public schools. So far, the Golf in Schools program is in 2,100 elementary schools and over 200 high schools in Canada, and they’re hoping to bring it to all 14,700+ such schools in the coming years. The funding for this comes from Golf Canada, who gets part of its money from member dues (i.e., the Canadian golfers) and part of it from the government.

2. Golf is a sport

The second thing that strikes you when you look at the differences between golf in America and golf in the countries that do well with women is the fact that it’s considered much more of a sport there than a social pastime. Women golfers in Germany, France and Sweden certainly enjoy the camaraderie of playing golf with their friends and family, but the golf course is viewed more as an athletic arena than a social scene. In most European countries, you’re not allowed to ride a golf cart unless you have a doctor’s affidavit proving injury or disability, and it’s not something people seem to want to do anyway. The beverage cart and cigar-smoking traditions we see on courses here in the U.S. are pretty much non-existent.

Another component that makes golf more of a sport in most northern and central European countries is the certification process that golf federations require new players to go through. In order to play as a beginner, new golfers must submit to a little bit of training with a pro and show that they understand the most common rules and etiquette requirements of the game. The details of the certification “test” vary from country to country, but beginners are essentially asked to demonstrate that they can move around the golf course at a decent pace, even if they’re not scoring well. Once they can do that, they’re given a “license” to play golf and a club handicap of 54. Until they drop below a 36 handicap, they’re required to play with golfers who are already below a 36 handicap in what becomes a sort of mentorship program. They learn more about the game from these players, and they also get to know other golfers this way.

Contrary to popular belief here in the U.S., this certification process is not a major hurdle to drawing new players to the game. The test is simple (second- and third-graders pass it every week) and actually has a positive effect, because it requires people to invest some time and energy in learning the basics from a professional, which draws them in faster. The subsequent licensingand mentorship programs help new players get more invested in the game, which keeps the retention rate higher.

3. Equality rules

Common denominator No. 3 among the countries that do well with women is an almost complete lack of gender bias within the golf facilities. Aside from a few older, private clubs in Canada (which are also changing their tune, just not as fast as the rest of the country), you will never see things like tee times, tournament days or different-sized locker rooms based on gender at golf clubs in these countries.

All tournaments except for the club championships are mixed-gender events—and also open to players of all ages. The certification process levels the playing field; as long as a golfer has been certified, his or her age and gender is irrelevant. Since all certified golfers carry handicaps based on the slope and course rating of the tees they typically play, there’s no misguided controversy over competing against players who use different tees.

The staffing at golf facilities in these countries is also very equal between men and women. There are no rangers profiling women’s groups, because the certification process eliminates the need for rangers entirely—golfers know how to play fast and how to let other groups play through. A twosome playing golf in Sweden could play through other groups half a dozen times in an 18-hole round. It’s simply the standard if you’re playing fast, and everybody knows how to make it happen seamlessly.

When asked how women are treated at golf facilities in their countries, most of the representatives I talked to acted puzzled, as if it was a trick question. “Why would women be treated differently than men?” was a common response. It’s simply bad for business.

4. A new spin

The countries that do well with women are not afraid to break with tradition. They’ve held on to important golf customs such as rules, sportsmanship and honor, but they’ve also joined the 21st century by getting rid of things like dress codes and mandatory 18-hole rounds. Play golf in Sweden and you’ll see someone in jeans on every other hole. Collars and sleeves may be missing from some shirts. When the weather is warm, everyone tries to catch a tan while playing golf, so there are tank tops and short shorts and even sandals in play. So far, it hasn’t compromised the integrity of the game, and it’s helped make golf the second-largest participation sport in the country.

Time is historically one of the biggest roadblocks for women when it comes to golf, which is why nine-hole rounds are much more accepted in these countries. Nine-hole rates are available almost everywhere, and many golfers play nine before or after work during the week, and then 18 on the weekends. Everyone knows how to submit nine-hole scores for handicaps, and there’s no social stigma among better players against playing “just” nine holes.

Another way these countries buck tradition is by using Stableford–or points–scoring rather than stroke or match play (in many places, it’s the basis of their handicap system, so it’s the recognized method), and there are a few benefits to this. First of all, it speeds up play; once you’ve reached a net double bogey on a hole, you pick up and move to the next tee. As a result, there is no shame in picking up the ball for new golfers—most players have to do it at least once or twice per round. The Stableford system also becomes a great equalizer, because golfers don’t talk about what score they shot in a round, just the number of points they racked up. The Stableford system also removes the need for Equitable Stroke Control and makes posting scores for handicaps a lot simpler for golfers of all abilities.

5. Breeding stars

An overwhelming number of the countries contacted for this project are putting a lot of effort and funding into breeding good junior players, especially in the wake of golf being named in 2009 as an Olympic sport. In some nations where government funding didn’t support golf in the past, national Olympic foundations now do. Some of these countries have already seen what having a big female hero can do to the growth of the game. The Olympics could be a massive game changer for growth in a way nothing golf has ever seen—as long as your country has the right players in place.

Improvement in the U.S. requires change

It would be easy to attribute the higher percentages of women golfers in the countries researched for this project to fundamentally different cultures—northern and central European nations are the most gender-equal in the world, whether you’re talking about politics, business, child rearing or religious leadership. But that theory falls flat when you take into account nations like South Korea. South Korea’s out-of-the-box thinking (simulator golf is the country’s biggest entry point for women golfers), paired with its first-class treatment of women at golf courses, has made golf an incredibly popular sport for females there (they’re up to 38%) despite its generally male-dominated society.

While the U.S. may never have a government entity overseeing and taking responsibility for the growth of golf, there are several things we can adopt from the countries that have high women’s-participation numbers.

For instance, the American golf industry could:

Institute a certification program for beginners and provide incentives for those who complete the certification process.

Institute mentorship programs and beginner tee times at golf courses.

Educate golfers on Stableford scoring and promote the system as an alternative to stroke play.

Make nine-hole tee times more easily accessible.

Encourage private and public courses to conduct at least one mixed-gender tournament per month.

Eliminate gender-influenced scheduling practices at public courses and put heavy pressure on private facilities to do the same.

Urge courses to implement new, more relaxed dress codes.

Site Powered by SR Computer Support – all rights reserved – Trademarks and brands are the property of their respective owners.